A Beginner’s Guide to Reading Clement of Alexandria

When I tell people I study Clement of Alexandria, they usually wish me good luck with his dense writing style or tell me they intend to read him but haven’t gotten around to it. I think both responses are completely valid. Clement’s writing can be difficult to grasp—particularly his Stromateis—and I’ve slowly grown convinced he was a more marginal figure than the canon of Christian history presents him. After having a couple people ask where they need to start with Clement, I thought it might be helpful to offer an introduction to his work with a low point of entry. So, here’s my beginner’s guide to reading Clement of Alexandria.

1. At the very least, commit to reading Clement’s full “trilogy”

The first step to reading Clement of Alexandria well is to come to grips with what you are signing up to undertake, especially if you are reading him in an English translation. Catholic University Press of America is working on completing an updated translation of the Stromateis, but only books 1–3 have been published in their Fathers of the Church Series. This means the Ante-Nicene Fathers (ANF) translation from Donaldson and Roberts remains the dominant English translation of Clement’s works. Their translation is generally good, but it feels dated because it’s from the late 1800s—and even their edition doesn’t translate one of the Stromateis’ books. Let the stale datedness endear you, and strap in for the ride.

Aside from the English translations available, Clement’s work is also most fruitfully read as a whole, forming a progressive curriculum. Although I think some scholars overrealize the relationship between each work, and I’m not quite sure it’s intended to be a “trilogy” per se, there is a clear direction that formation is intended to take as a reader moves from the Protrepticus, through the Paedagogus, and into the Stromateis. My advice is this: if you plan to read Clement, commit to reading all three of these works in their entirety. Read them in full, and read them in that order. If you want to read the other surviving writings or fragments, that’s fine, but these three works clearly have the most staying power and provide the clearest image of the Clement of Alexandria passed down to us in the church.

2. Learn about the Second Sophistic

To be clear, I don’t intend to suggest you have to become a classics scholar focused on the Second Sophistic. However, if you want to get the most out of Clement, you need to be able to situate him within his cultural setting appropriately. As Jane Heath and Stuart Thomson have sufficiently demonstrated, Clement intentionally draws upon shared cultural literary aesthetics of the Second Sophistic to write his work. Given that the Second Sophistic was a time of heightened anxieties about cultural identity which resulted in innovative literary practices, Clement’s creativity as an author is brought into sharper relief when you recognize these connotations within his work.

If you plan to read the Stromateis in particular, you would be well-served to spend an afternoon reading a few introductory articles about the Second Sophistic. Learn about the social, cultural, and political impulses that led to so many prolific and flowery writers. Clement takes his literary cues from authors within a similar timeframe, like Pliny, Plutarch, and Gellius. Their miscellanies—long, winding, variegated forms of writing without a “conventional” structure or argument—were the medium Clement chose to use for his project. Giving a little attention to the background of these ideas and authors will help you see how Clement capitalizes upon the literary miscellany to accomplish his curriculum of spiritual formation.

A good starting place for the Second Sophistic is Tim Whitmarsh’s short (~100 pages) introductory volume. William Fitzgerald’s book on variety in Roman life is a good contextualization, too, though it’s less focused on the Second Sophistic proper and more about some consequential cultural phenomena tangential to it.

3. Treat his texts as interactive

One of the most profound aspects of Clement as an author is his ability to silently encode the need for participation, attention, and application throughout his writing. Especially regarding works like the Paedagogus and the Stromateis, treat the text as an interactive reading experience. While both texts are clearly moral in nature, the Paedagogus intends to shape the Christian life in a direct manner. The Stromateis, on the other hand, is better consumed in very large chunks, often requiring rereading several times over as the reader brings the fraying threads of the work into one unified principle. Don’t be afraid of the diversity and breadth of the text; rather, lean into it. The real value of Clement’s works emerges from the activity of reading them.

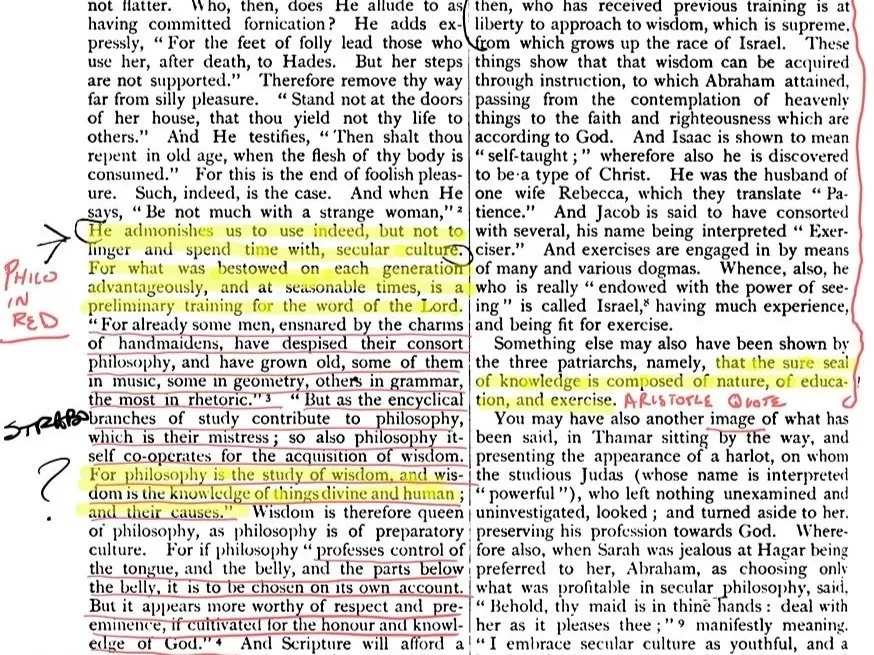

Here’s an example of what my copy of Clement looked like as I read him several times over for my dissertation:

When it comes to understanding the Stromateis, it is perhaps most efficient to treat it like a web of theological reflections which trap the reader. It allows you to recognize the intertextual references, relationships between big ideas, and the argument unfolding on a macro level. This writing style is an authorial decision to wield a specific way of teaching and organizing knowledge—it allows you as to do the work of piecing together the truths Clement conceals through his verbosity. Don’t try to prooftext or mine Clement for soundbites; you won’t find them, and there is a chance you will misunderstand them if you do. Rather, compile notes along your way as you try to connect the constellation of ideas within his writings.

Clement’s writing is best enjoyed like a long meal that doesn’t fill you until you’ve reached the end of the final course. Then, and only then, can you look back at the sum of the courses to realize the entire evening had been a delight.

Conclusion

Following even these simple, low-stakes tips would make you a far more patient and perceptive reader of the Stromateis than many in the recent past. Clement has a reputation for being esoteric, excessive, and unorthodox (in many senses of the term). Approaching Clement with an open mind that doesn’t impose the expectations of contemporary systematic literature, however, reveals the ways that Clement can be a helpful guide into Christian formation.

Recommended Clementine reading

Here are a few quick blurbs for recommended scholarly readings on Clement. You certainly don’t need these to benefit from reading Clement on a personal level, but if you are curious on taking a deeper dive, these will introduce you to the lay of the scholarly land:

Jane Heath’s Clement of Alexandria and the Shaping of Christian Literary Practice: Miscellany and the Transformation of Greco-Roman Writing is one of the most significant contributions to the topic of Clement in a very long time. I really do think it’s hard to do scholarship on Clement well without grappling with her work.

Doru Costache’s Nature Contemplation in Clement of Alexandria and Humankind and the Cosmos. Obviously only one of these is fully dedicated to Clement; however, both books cover ample territory that help you understand Clement’s approach and posture toward theological reflection. Humankind and the Cosmos has a few really strong sections dedicated to Clement’s works (and the non-Clement portions are fun to read, too).

Other works worth your attention: H. Clifton Ward’s Clement and Scriptural Exegesis, Piotr Ashwin-Siejkowski’s Clement of Alexandria: A Project of Christian Perfection, and Andrew Itter’s Esoteric Teaching in the Stromateis of Clement of Alexandria are all worthy readings of Clement’s project that bring much to the table.

Lastly, Lux Patrum is in the process of producing diglot editions of Clement’s writings that will inevitably make the cost of entry for reading him much lower.